As recently as 2015 the NY Office of the State Comptroller named Potsdam the most fiscally stressed village in NYS. How did this happen and can it happen again? Fiscal stress typically occurs when revenue plummets and/or expenditures balloon.

Revenues derived from property taxes are steady and predictable but account for about 25% of all village revenue. The remaining revenue sources are far less predictable. For example, our revenue decreases if sales taxes decrease. As recently as October 24, 2023 an article headlined “September tri-county sales tax receipts down significantly from 2022” stated that St. Lawrence County receipts were down $1.36 million from a year ago, a significant 6% drop (1). During the previous budget year of 2021-2022, for example, the village received $1.8 million in sales tax revenue, so every 1% reduction in sales tax revenue amounts to a loss of nearly $20,000 to the village. If sales do not pick up, the village could face a revenue shortfall of around $100,000 this budget year.

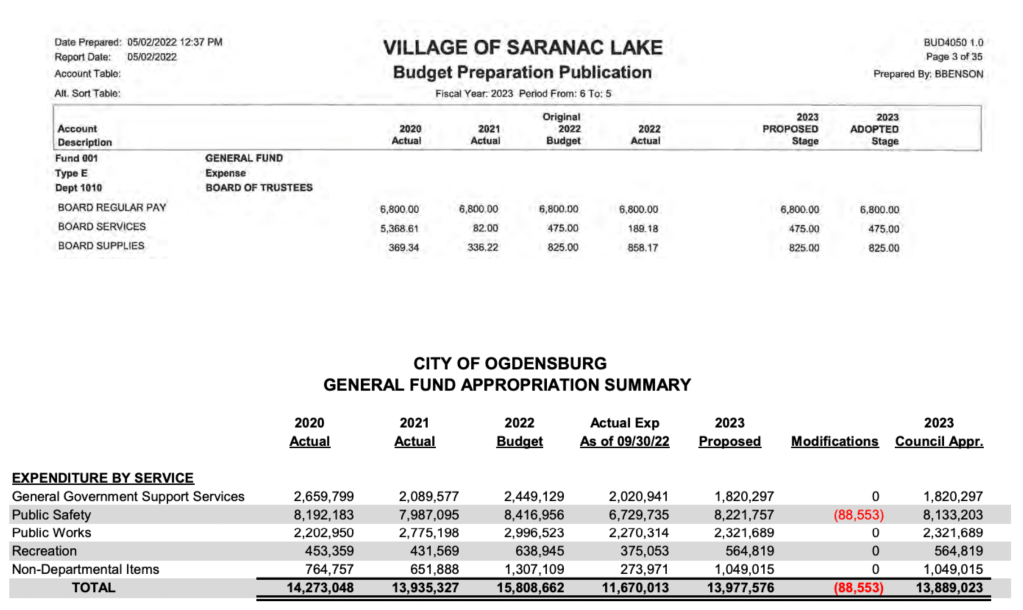

The village opted in the summer of 2021 to dissolve its recreation partnership with the town which resulted in a yearly loss of $160,000 to the village (2). While the village expected to reduce its recreation budget without the responsibility of Postwood park, the opposite is true: Recreation appropriations went up, not down, by over $20,000 in FY23 and FY24, from an appropriation of $500,000 in 2022 to over $520,000 each of the next two years.

Revenues also decrease if anticipated fee incomes decline. Last year, for example, the village received around $500,000 for building permits associated with the CPH addition. The village also received a non-recurring payment of $425,000 for the sale of a portion of Cottage St. These non-recurring boosts to the budget are wonderful but atypical (The sale of Cottage St. provided most of the funding for the new pickleball courts).

State and Federal funding for village projects are also highly variable. The recent generous pandemic funding is drying up as State and Federal governments adjust to massive debt burdens combined with higher interest rates.

Finally, village income decreases if actual expenditures exceed budgeted expenditures or appropriations, as this results in a loss of interest income. At the end of May 2022 the village held over $6 million in the bank, earning an interest in excess of 5%, or over $25,000 per month. Hence for every $100,000 reduction at the bank (due to expenses exceeding appropriations), the village loses around $5500 income annually. Overspending our allotted budget by $1 million equates to a revenue loss from interest of around $55,000.

How might actual expenses exceed budgeted expenses? The budget is designed to withstand some surprises, as when trucks break down or medical coverage is required for an employee. The Treasurer might reallocate moneys from various “contingency” lines to the line-items needing additional funds. This works well until the contingency sources run dry, at which point funding the un-anticipated or non-budgeted would require dipping into the village cash reserves or savings.

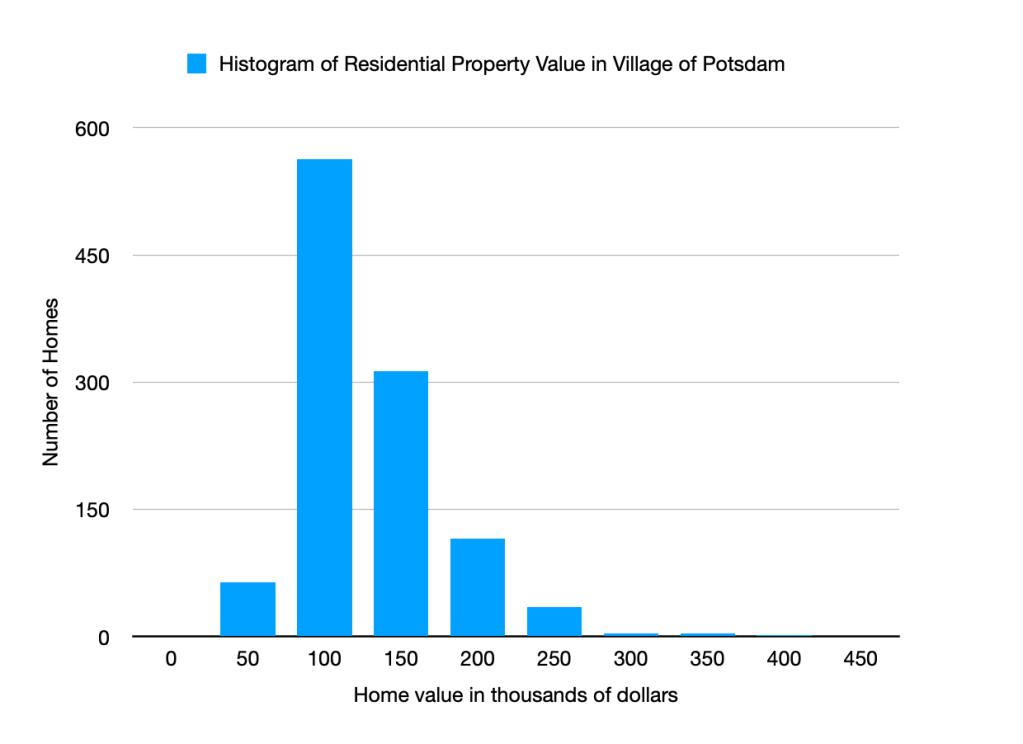

This has happened before: the village’s general fund balance decreased from over a $1 million excess at the end of the 2011-2012 budget year to a $15,911 deficit at the end of 2014-2015. That’s when the office of the state comptroller named Potsdam the most fiscally stressed village in NYS (there are 530 villages in NYS). The village had to borrow $500,000 to pay employees. To reduce expenditures, the board abolished the village justice court and increased village tax rates from $15.06 per thousand dollars in property value in 2013-2014 to $18.29 per thousand since 2018-2019. (At the end of May 2022, village cash holdings stood at an impressive $6.3 million. As the emergency requiring the elevated village tax rates ended, the board opted to use $250,000 of these savings to reduce this year’s village tax rate to $17.16).

Why did our savings vanish in 2015? One can read the details in a NCPR article by Lauren Rosenthal dated 3/10/2016, but the bottom line seems to be that the village board voted to use $1.6 million in cash reserves to pay for the many cost-deficits associated with its municipal hydrodams(3). Unfortunately, that danger persists today. For budget year 2021-2022 (the latest published), the hydrodams earned a combined $76,000. That income is likely to decrease this year as the Village Administrator recently informed the board that the blades on the East Dam rotors (the only functioning hydroelectric facility) can no longer be adjusted, leading to significant loss of power production. But the 2023-2024 budget did have to allocate $570,000 towards its Hydro Fund ($430,000 towards debt payments, $90,000 towards operating expenses, $30,000 towards fringe benefits for workers, plus a $20,000 contingency). The difference between the overall cost to the village to run its municipal hydrodams, $570,000, less the revenue generated by those dams, maybe $50,000, equal to $520,000, will be paid for by village tax dollars.

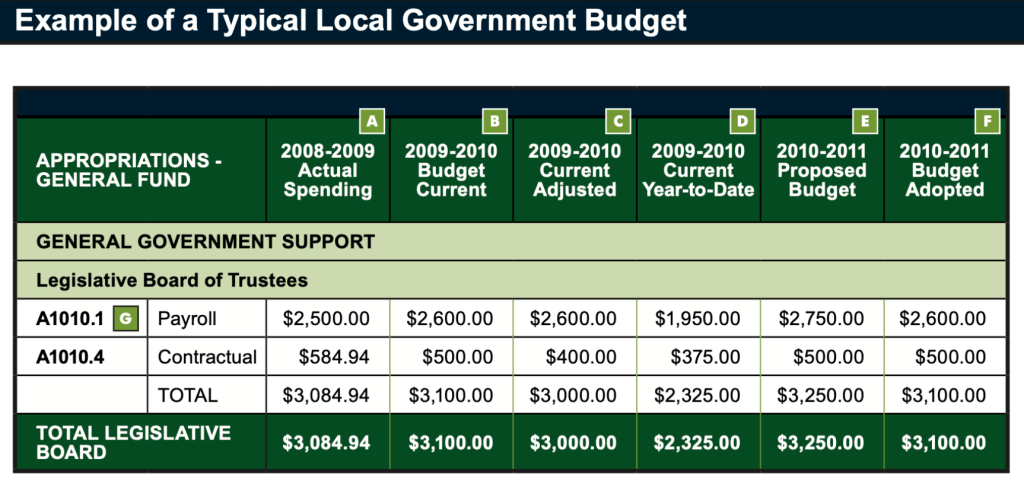

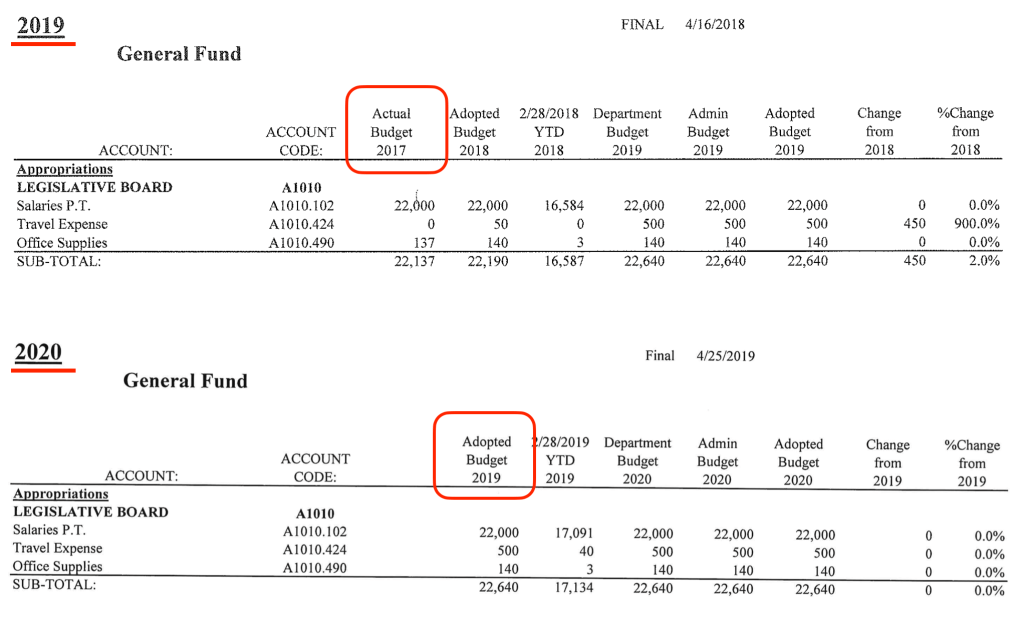

And so, yes, I think it is possible for a not-so-perfect storm of lower-than-anticipated sales tax revenue, fees and reduced federal and state funds might lead to a reduction in our cash holdings and interest earnings. Combine these income reductions with increasing costs for workman comps (an annual increase of $40,000 is anticipated), salary and fringe benefits, materials, labor and IT services, we could well run into fiscal stress once again. Without expenditure sheets to guide the board, only appropriation requests as explained in a previous post (4), it is impossible to extrapolate future spending trends based on past expense patterns.

Sources:

(1) nny360.com/news/stlawrencecounty/september-tri-county-sales-tax-receipts-down-significantly-from-2022/article_6dac9881-7435-5b05-a715-783b0e153a31.html

(2) nny360.com/opinion/editorials/editorial-diving-in-town-of-potsdam-will-assume-all-control-of-postwood-beach/article_1436bbf5-225e-5991-921e-f47493df0861.html

(3) northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/31231/20160310/how-did-potsdam-become-the-most-fiscally-stressed-village-in-the-state

(4) villagemusings.org/2023/10/13/the-mystery-of-6-years-of-missing-expenses/