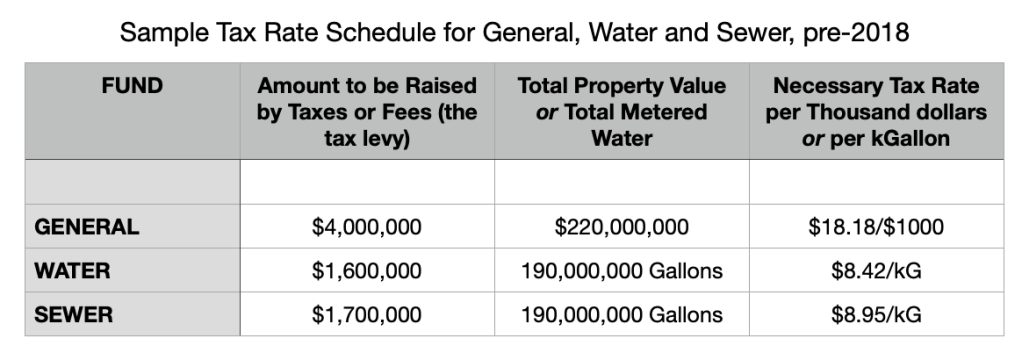

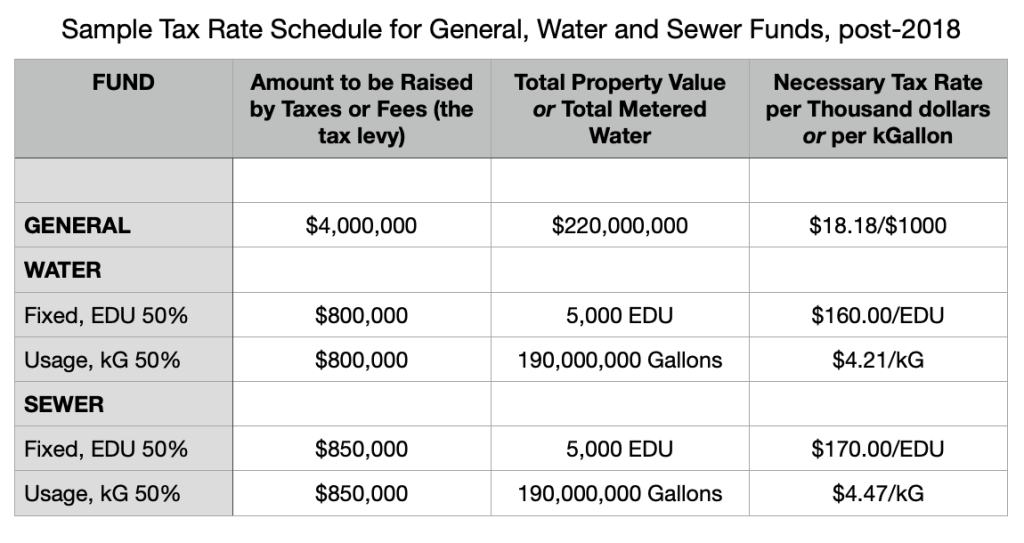

Prior to 2018, the village of Potsdam, like most municipalities, billed for water and sewer according to how many thousand-gallons of water (kGallon) were used per customer. In the sample tax rate schedule below, the tax rates for three funds are presented.

The General Fund, as described in an earlier post, typically needs to raise $4,000,000 from the total taxable property value of the village. The total taxable property value of the village is close to $220 million. So therefore the necessary village property tax rate for every thousand dollars of property value is $4,000,000/$220,000=$18.18

Similarly, the Water Fund might need to raise $1.6 million from water taxes (which are termed water rents). How many total gallons of water are billed for in the village annually? It is close to 190 million gallons. So prior to 2018, to raise the needed water-tax levy of $1.6 million, the water tax rate for every thousand gallons of water had to be set to $1,600,000/190,000kG = $8.42/kG.

Similarly, the Sewer Fund perhaps needed to raise $1.7 million from sewer taxes (termed sewer rents). The number of gallons of sewage generated is assumed to equal the number of gallons of water billed. So the sewer tax rate (sewer rent) required to generate $1.7 million of revenue equals $1,700,000/190,000kG = $8.95/kG. (This information is required, by law, to be published in the budget reports filed on the village website, and is typically found on the second to last page of the documents: see vi.potsdam.ny.us/treasurer )

Everyone more or less understood these things. But the problem the village had was that whenever the water and sewer tax rates were increased (to perhaps pay for some expensive repair or piece of equipment at the water or sewer departments), people would conserve water accordingly, so that their billing remained level. Revenues therefore did not increase and either or both funds went into the red. Frequently.

So starting in the early 2000s, municipalities all over the country began to divide their water and sewer billing into a usage portion as well as a fixed portion. Everyone would pay a mandatory, fixed portion, whether they used any water or not, plus a usage portion. This resulted in tax rate schedules like the one below. In the case of our village, 50% of the water (sewer) levy is raised from the fixed portion and 50% is raised from a usage portion. So the tax rates for the usage portions are exactly half their previous rates (the usage levy is 50% of $1.6 million = $800,000 while the total number of gallons of water billed remains at 190 million gallons). But whence the fixed water and sewer tax rates?

Each user (or account) would be assigned an EDU (Equivalent Dwelling Unit) value. Single family homes, for example, all receive an EDU assignment of 1. A two family home receives an EDU assignment of 2. And businesses and nonprofits obtain EDU assignments based on how much water they use: so a laundromat or a car wash would get a higher EDU assignment than a minimart, for example. (One EDU is equal to 120 gallons of water use per day). To see who gets how many EDU, see our online local laws:

ecode360.com/attachment/PO0885/PO0885-173a%20Appendix%20A.pdf

Given that the total number of water and sewer EDUs assigned throughout the village is 5000 EDUs, then the water-tax rate required to raise $800,000 is $800,000/5000EDU = $160.00/EDU. Similarly, the sewer-tax rate required in order to raise $850,000 is $850,000/5000EDU = $170.00/EDU.

This would be a good place to end this discussion, but let me continue to itemize my concerns with the system as implemented by our municipality. Businesses, for profit as well as non-profits, have changed their water use significantly over the years (especially during and after Covid), yet their assigned EDUs have never been adjusted. This creates significant inequities. In addition, while water and sewer tax levies have been adjusted, tax rates have not been adjusted accordingly. This makes the accounting of fund balances and encumbrances dubious. Without clear numbers on whether each fund is growing, shrinking or holding steady, the Board can not set prudent tax-rates.